OCELLATED DRAGONET

Success With a Model Species

As a major participant of the Rising Tide Conservation Initiative, University of Florida’s Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory is attempting to raise small-egg, pelagic spawning species that many would consider impossible. Surgeonfish and angelfish, butterflies and anthias…These species rank among the most heavily traded reef fishes yet we know very little about their natural history requirements and how to raise them in captivity. Raising such a fish is no small feat, but we are cotinually excited by smaller victories along the way. In our quest to fulfill the quixotic dream, we are using model pelagic spawning species to help answer detailed questions about development, incubation, feeding, and environmental constraints to survival.

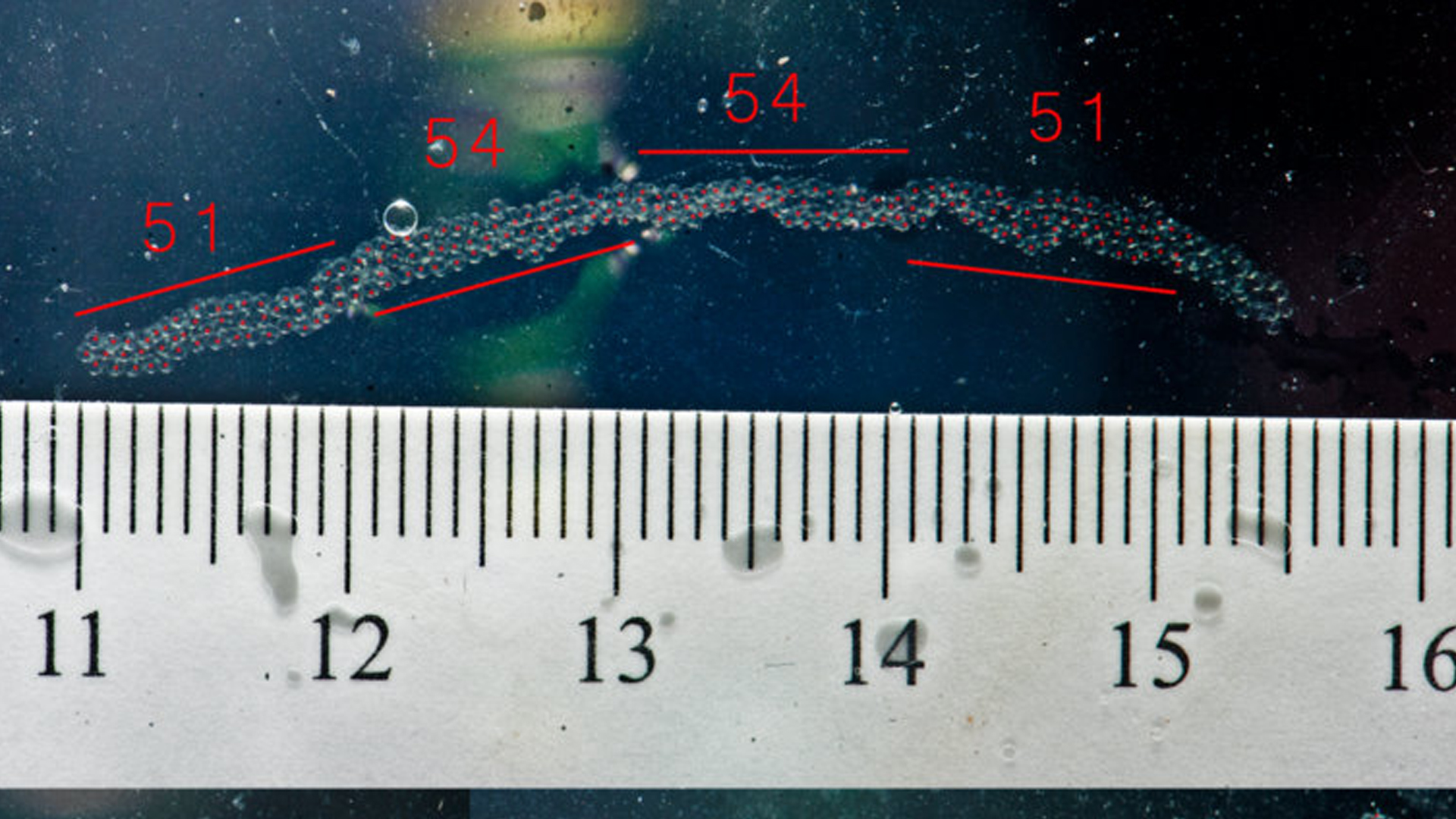

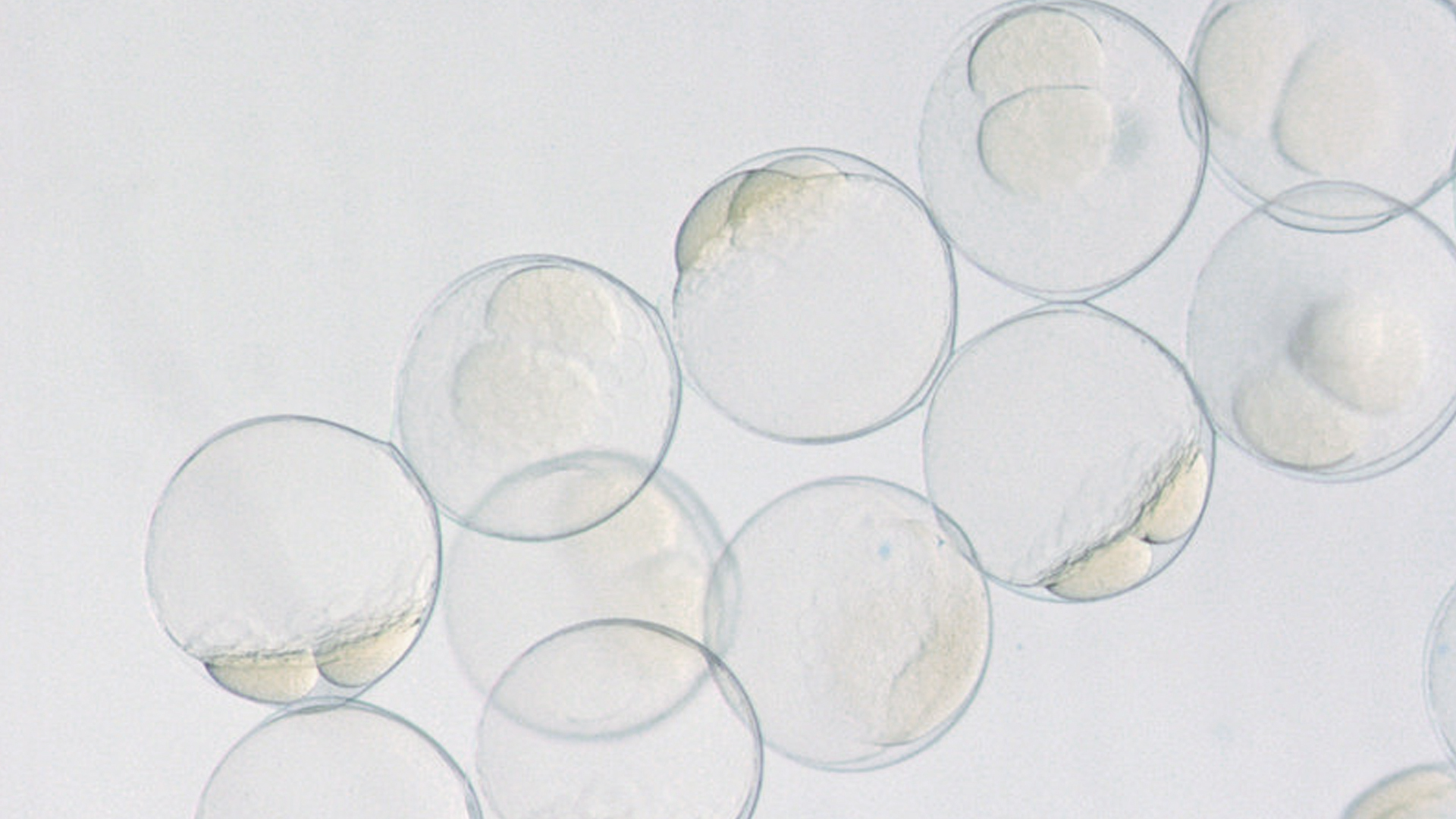

Over the last few months we have experienced difficulties incubating and hatching pelagic eggs spawned by some of our captive broodstock. Before tearing our hair out, we came up with a plan to use a model pelagic spawning species to help solve some of our problems. I have worked with several dragonet species over the years and felt confident that I understood enough of their development to use them as a reliable model. Segrest Farms donated 20 ocellated dragonets (Synchiropus ocellatus) that we quickly conditioned into a reproductive state. We set up two broodstock colonies with each tank producing ~ 3,500 eggs each evening. Ocellated dragonet eggs are spawned in chains that hold together as they drift toward the surface. This not only faciliates egg collection, but also makes egg counts relatively easy. We were able to estimate with reliable accuracy the number of eggs in a cm of egg strand and then simply measure the cumulative length of egg strands collected each evening.

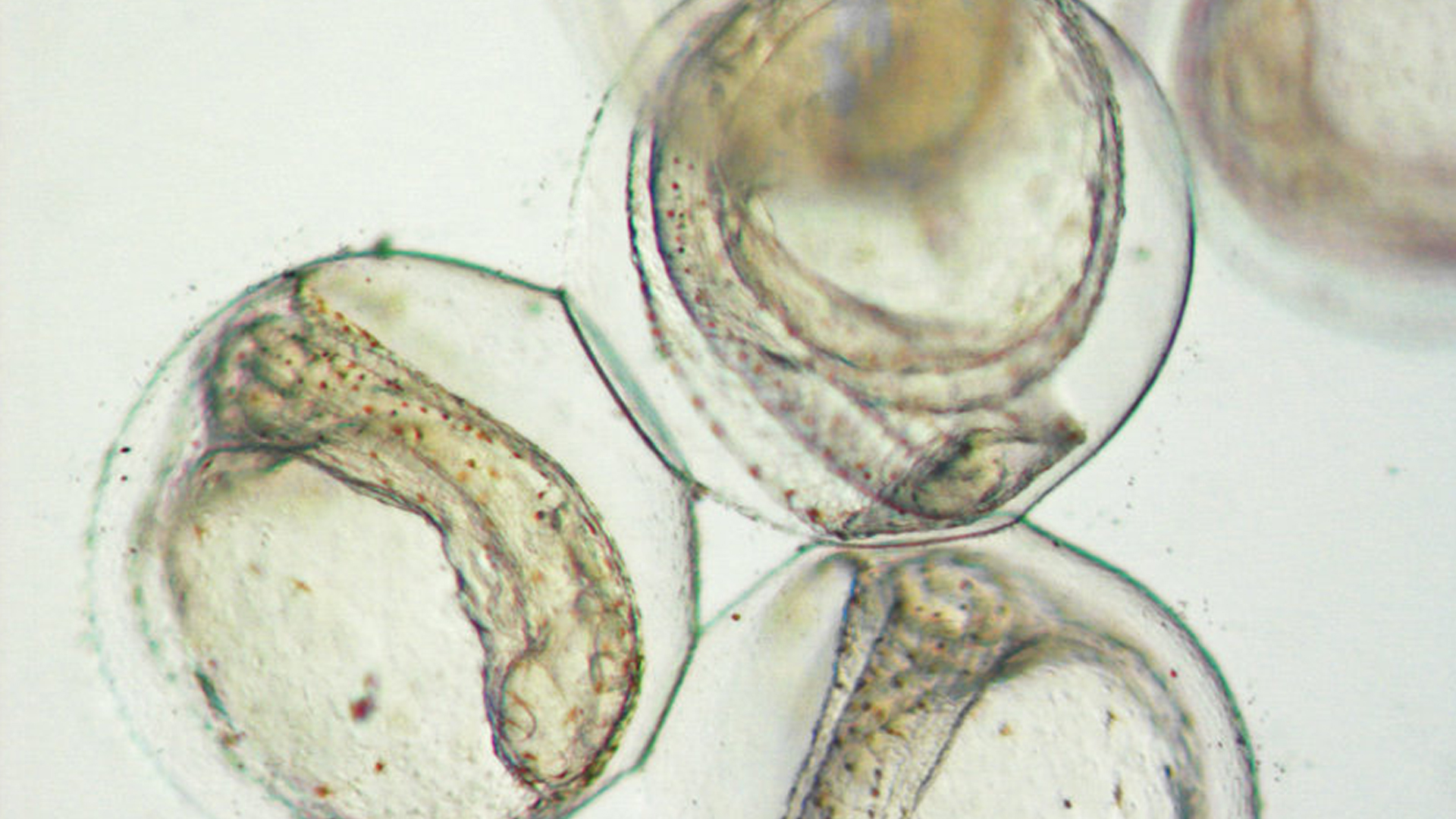

Unlike most dragonet eggs that hatch in 12 – 16 hours ocellated dragonet eggs take up to 32 hours to hatch. Because of this, water quality during incubation is extremely important. Eggs are sensitive to degradation of water quality and microbial build up.

First feeding is initiated 3 days after hatching and creates the crucial first step in whether a larval rearing attempt is successful or not. Mouth gape is a major constraint as the tiny larvae just can’t fit many zooplankton organisms into their mouth. Most larvae though, consume prey that is less than 20% of the maximum gape – in the case of the ocellated dragonet this means prey that is only 40 – 50 microns. Unlike the larvae of the green and spotted mandarins that accept copepod nauplii as a first food, ocellated dragonets need something smaller. To bridge the gap with commercial diets and foods that we know we can reliably produce UF researchers Eric Cassiano, Christine Creamer and myself have been exploring the efficacy of alternative first foods. We use a proven approach that starts with the ocean. First, we offer controlled densities of size-sorted wild zooplankton to observe what the larvae ‘choose’ to eat. Then, we attempt to culture the organisms identified and test survival rates with the different prey organisms. We were successful in identifying a ciliated protozoan that was consumed by larval dragonets and bridged the gap with a copepod diet.