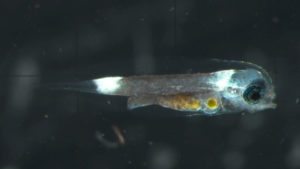

Since the majority of marine fish larvae do not readily accept rotifers as a first feeding organism, the approach at the Tropical Aquaculture Lab has been to utilize their ‘natural’ prey in the hopes of identifying a candidate prey species for intensive culture. When the marine fish larvae reach first feeding they are provided size sorted wild plankton. We are lucky enough to be located only a few minutes from Tampa Bay, so a (somewhat) reliable source of plankton is always within arm’s length. We typically pull a plankton net along a dock within our local park. On occasion we’ll take out the boat and pull the net behind the boat. The net has a mesh size of 50 microns, so everything larger than that gets collected and brought back to the lab. Smaller organisms often get caught as the mesh clogs. At this point, we have concentrated plankton which is then sieved through a 300 micron mesh to separate out the larger debris (leaves, ctenophores, etc.). The plankton is then placed under heavy aeration to provide air and circulation to an overcrowded population but also settles out some of the unwanted smaller detritis that was collected as well.

Plankton net used at TAL. Photo credit: Eric Cassiano.

After a few hours the plankton is ready to be fed to the fish larvae. Depending on the species involved, we will sieve the plankton again to provide appropriately sized prey. Typically, we begin feeding larvae at 125 microns and below. We usually have multiple cohorts so the larger plankton gets fed to the older larvae. Prior to feeding we take note of prey species composition and feeding density; which can be quite plentiful. After a few hours of feeding, we sample larvae in the hopes of identifying if and what they’re eating. We have made some advances with a few species of fish larvae and live feeds; which I’ll talk about in upcoming posts. However, some gut contents are unidentifiable to the trained eye and therefore we’re exploring the use of DNA technology to correctly identify specific prey items. This will greatly streamline our research efforts and yield a significant amount of first feeding information. Furthermore, we currently only provide plankton available in Tampa Bay; which may or may not contain the appropriate prey for all the species examined. Feeding fish larvae wild zooplankton is not suggested as a commercial production model; possibly containing pathogens detrimental to production. Again, we only use it as a screening process to identify possible candidates for intensive production.