It is hard to believe that just 15 days ago we were trying to figure out what the transparent eggs from Discovery Cove might be. Just a few days into the larval run we knew we had a diversity of species. A few of them, in particular, caught our attention. In the same tank as the tiny holocentrid larvae, swam hundreds of grunts, and perhaps 2 or 3 oddball larvae that stuck out like a sore thumb. They had a characteristic large, bulbous head, that glowed orange in the green tinted water. They seem to swim in a determined, but clumsy fashion. These larvae didn’t seem particular fussy about food, but they developed a fondness for slightly larger morsels. After about 8 days of development these large, orange-headed larvae were definitely the largest fish in the tank. Watching them for a few minutes would reveal the other fish darting away when one of them approached. It soon became apparent why.

I had just fed out a small size class of plankton and watched intently; looking for signs that the holocentrid larvae were feeding. Out of the corner of my eye I saw a silver flash from a distressed larva. This isn’t particularly rare in a heavily stocked tank. Swirling, disoriented larvae are a sure sign that water quality is deteriorating, bacteria is becoming a problem, or the fish are starving. In this case, however, the larva was being sucked in, spit out, and rearranged for consumption by one of the oddball larvae. It turns out, they liked to eat smaller larvae.

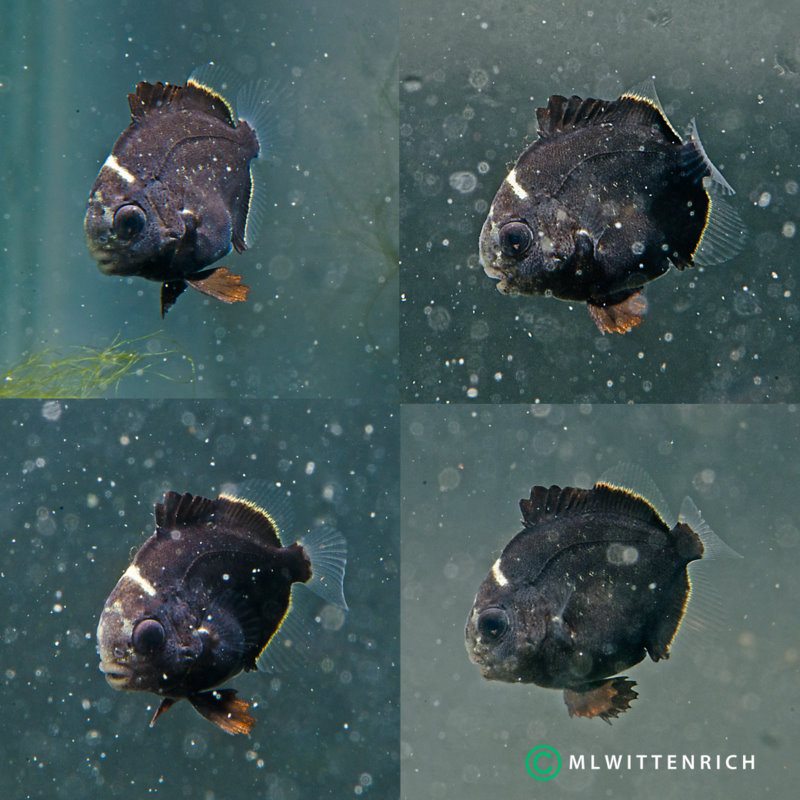

15 day old spadefish collected as eggs from Discovery Cove and raised at the Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory

Fifteen days after hatching the larvae completed metamorphosis and became oriented to structure. In fact, the now juveniles seem hesitant to swim any distance away from the wall or airline tubing. I am convinced that these hardy juveniles are spadefish, Chaetodipterus faber.

This isn’t the first time spadefish have been reared, and in fact, far from it. I first heard of spadefish being reared at the Tulsa Zoo by Stephan Walker. Stephan published a great article in SeaScope detailing his success with the fish. In a similar fashion, Stephan was successful in harvesting eggs spawned in a large exhibit at the Tulsa Zoo.

Today, as I was searching for images of what a spadefish juvenile might look like I stumbled across a Virginia Seagrant funded project that was exploring large-scale spadefish culture for food.

All of these observations show that the larval phase of spadefish is quite conducive to large scale culture. The team at Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) and the Southern Illinois University at Carbondale collected wild juveniles and raised them for a year in captivity before hormonally inducing spawning. Sexual maturity is attained in a year, the larvae are voracious feeders of traditional aquaculture fare such as rotifers and Artemia, and reach metamorphosis in only 15 days, when they are slightly smaller than a dime.

It is likely that all members of the Ephippidae reproduce and develop in a similar fashion. These little spadefish should be going home to Discovery Cove in a few months and we are hopeful that we will have an opportunity to try our hand at rearing other members of this popular family.

Special thanks to Dense Swider and the team at Discovery Cove for all of their hard work and dedication.

Stephan D. Walker’s article in SeaScope

Matthew L. Wittenrich, PhD | Senior Biological Scientist

Eric Cassiano | Biological Scientist

Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory | University of Florida